01 December, 2020

The Nightingale: Music, Poetry & Literature (I)

Ancient Times (up to 1500 AD)

The sweet songs of nightingales have enamoured humans from the dawn of time, it seems, or at least from the dawn of culture, where we found ways to transform our beliefs and worries, our dreams and awe into words, music and art. We find the nightingale tucked into the furthest recesses of human culture, its nocturnal warblings metamorphosing into a metaphor for artists, paramours and poets over time, feverishly burning the midnight oil in the pursuit of art, love and beauty.

The bird’s midnight music has often been linked to sorrow, a mournful song under cloak of darkness, a poetic license that is linked to the nightingale’s associations with grief in Greek mythology. We find it in Homer’s Odyssey, alluding to the myth of Aedon who accidentally slew her son Itylus, and in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, in the tragedy of Philomela and Procne, turned into a swallow and a nightingale respectively. As this story was later translated into Latin, most of the writers interchanged the two birds, so that Philomela is now more famously associated with the nightingale. Plato contradicts this tragic portrayal of the nightingale’s lament in his Phaedo, where Socrates refutes the idea that any bird sings in mourning – though this didn’t stop the artistic association between nightingales and sorrow for some time.

F.Hecker; Picture Alliance

As we prepare to offer up our own gifts of music to the nightingale next spring for Singing With Nightingales, we’ve delved into the annals of cultural history to find where the nightingale has left its mark. Here are some literary highlights from what we’ve loosely called ‘Ancient Times’, up to 1500 AD:

C4th BCE – Plato – Phaedo

But men, because they are themselves afraid of death, slanderously affirm of the swans that they sing a lament at the last, not considering that no bird sings when cold, or hungry, or in pain, not even the nightingale, nor the swallow, nor yet the hoopoe; which are said indeed to tune a lay of sorrow, although I do not believe this to be true of them any more than of the swans. But because they are sacred to Apollo, they have the gift of prophecy, and anticipate the good things of another world, wherefore they sing and rejoice in that day more than they ever did before.

C7th-8th BCE – Homer – The Odyssey (Book XIX)

As the dun nightingale, daughter of Pandareus, sings in the early spring from her seat in shadiest covert hid, and with many a plaintive trill pours out the tale how by mishap she killed her own child Itylus, son of king Zethus.

Tereus, Philomela & Procne

C1st – Ovid – Philomela – Metamorphoses (Book VI, 653-674)

You might think the Athenian women have taken wing: they have taken wings. One of them, a nightingale, Procne, makes for the woods. The other, a swallow, Philomela, flies to the eaves of the palace, and even now her throat has not lost the stain of that murder, and the soft down bears witness to the blood.

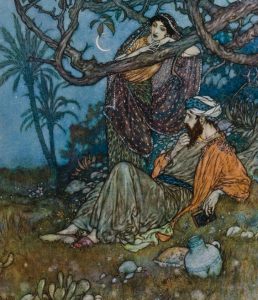

Edmund Dulac, 1909

C12th – Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

Translated by Edward Whinfield in 1822 from eight medieval manuscripts. The work is not of a single author, but has been contributed to by many hands over the centuries, with the astronomer Omar Khayyam who died in 1132 made into the frame author.

Into the garden flew a drunken nightingale,

delighting in the cup of wine that was its rose.

It whispered with its mystic voice into my ear:

“Grab hold, since life–once lost–cannot be had again.”

The Owl and the Nightingale Manuscript

C12th-13th – The Owl and the Nightingale

This is the earliest example in Middle English of a literary form known as debate poetry (or verse contest).

Jesus College Edition:

Þe Nihtegale bigon þo ſpeke

In one hurne of one beche

& sat vp one vayre bowe.

Þat were abute bloſtome ynowe.

In ore vaſte þikke hegge.

Imeynd myd ſpire. & grene ſegge.

[lines 13–18]

Modern English translation:

The Nightingale began the match

Off in a corner, on a fallow patch,

sitting high on the branch of a tree

Where blossoms bloomed most handsomely

above a thick protective hedge

Grown up in rushes and green sedge.

Listen to Sam Lee talking to Simon Armitage about the poet laureate’s translation of The Owl and the Nightingale: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p088vbx0

The Book of Cupid

C14th – Sir Thomas Clanvowe – The Cuckoo and the Nightingale (or The Book of Cupid, God of Love)

This poem was attributed to Chaucer for a long time, only being correctly attributed to Clanvowe in the 1890s.

But as I lay this other night wakinge,

I thoghte how lovers had a tokeninge,

And among hem it was a comune tale,

That it were good to here the nightingale

Rather than the lewde cukkow singe.

And then I thoghte, anon as it was day,

I wolde go som whider to assay

If that I might a nightingalë here;

For yet had I non herd of al this yere,

And hit was tho the thridde night of May.

Join us for Singing With Nightingales in April/May 2021, in Sussex and Gloucestershire.